It’s bad enough that water utilities project far more supplies than they have access to which by definition is paper water. It's bad enough that using this imaginary water they always come to conclusion that every project requesting a WSA has sufficient water to proceed. But recently it became clear to me that are other forms of paper water that comes in large amounts as well. Paper water by definition is water the city says it has available to it, but it can never access because it’s being used by someone else within the state's water system.

In July I was asked by the Banning Ranch Conservancy to look at the Newport Banning Ranch water supply assessment as they prepared for a California Coastal Commission meeting on the project. Having reviewed quite a number of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power water supply assessments I knew the first place to look for paper water would be in found in the utilities projections. Over time I've suspected there were other areas where paper water could be found but L.A.’s sheer size made it difficult for me to validate those.

In July I was asked by the Banning Ranch Conservancy to look at the Newport Banning Ranch water supply assessment as they prepared for a California Coastal Commission meeting on the project. Having reviewed quite a number of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power water supply assessments I knew the first place to look for paper water would be in found in the utilities projections. Over time I've suspected there were other areas where paper water could be found but L.A.’s sheer size made it difficult for me to validate those.

Reviewing this projects WSA was a good opportunity for me because it is more typical of WSA’s that are produced throughout Southern California and the city’s relatively small population also made it easier to see whether housing growth can contribute to paper water ‘surpluses’ under SB 610.

For a little background, the Newport Banning Ranch (NBR) project is a proposed 1,375 housing unit development in the City of Newport Beach that also includes commercial. The city’s water supply is quite a different from the City of Los Angeles's water supply in that groundwater clearly is a substantial portion of the city's water supply. Newport Beach does not have its own domestic ground water supply underfoot but instead it has four wells that are located are located about five miles away in Fountain Valley which are managed by the Orange County Water District. When ground water is in short supply the city buys imported water from MWDOC.

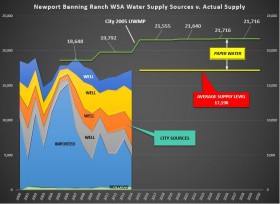

When I dug into the Newport Banning Ranch WSA I found it was similar to the water supply assessments that are routinely produced by the LADWP. The Newport Beach water supply assessment relies heavily on 'paper water' to create a façade of surplus water just like L.A.'s water supply assessments. When reviewing the city’s sources of water supply, I found that they never met their respective supply projections and there was no chance that they ever would. 21 percent of the city’s projected water supply was water that the city didn't have access to. Hence it was ‘paper water.’

Growth’s Contribution to Paper Water

But there was more. What about housing that doesn’t trigger SB 610 requirements for a WSA? Failing to report cumulative housing construction would be another form of paper water. If a WSA doesn’t acknowledge that new housing has been constructed since the city’s Urban Water Management Plan was approved, the water demand from the unrecognized housing would be viewed as a unused water that is still available for new projects.

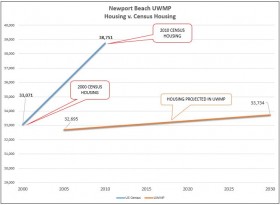

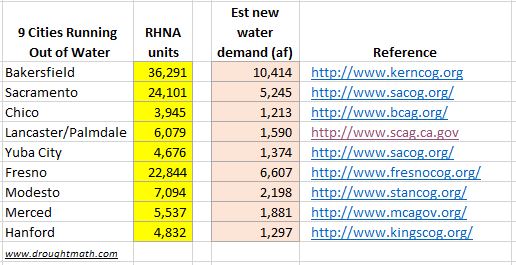

The Newport Banning Ranch water supply assessment was based on an increase of just 1,039 housing units over 20 years. That figure came from the city’s Urban Water Management Plan which in turn comes from the RHNA allocations that are imposed on cities. A subject that I’ve written about extensively here.

The Newport Banning Ranch water supply assessment was based on an increase of just 1,039 housing units over 20 years. That figure came from the city’s Urban Water Management Plan which in turn comes from the RHNA allocations that are imposed on cities. A subject that I’ve written about extensively here.

Right off the top, the NBR project's proposed 1,375 units exceeds the city’s 20-year water plan by 336 units meaning that new water supplies should have been identified in the WSA.

But that led me to the next question. Aside from the fact that the project is larger the city’s projected housing growth, how many units were built in the city since 2005 that did not trigger a water supply assessment? The answer was stunning.

In just five years the city’s rise in housing exceeded the UWMP's 20-year projected growth by 380% or 5,017 units and there was still fifteen years to go. The extent of this growth really surprised me. I didn't expect that growth could be so under-projected in a UWMP that it would decidedly tip the scale towards insufficient supplies in just five years. Shouldn't a water supply assessment capture this demand on water supply? I think so. You can't say your Showing Me the Water if your not disclosing the demand.

Not surprisingly, the water supply assessment didn’t acknowledge this new housing so this water could be viewed as an unused surplus. The project's WSA simply ignored the new housing. Had it acknowledged that the city had grown, it may have created pressure on the developer to find new water supplies. The Show Me the Water Law is supposed to link large projects to water supply. It should also assure that large projects are not be claiming to have access to water already that has already been committed elsewhere.

SB 610’s silence on projects that are less than 500 units effectively guts the law. The law only says that a WSA must include a ‘discussion’ of various elements of the water supply such as total projected supply during normal and dry years. The law doesn’t explicitly point out that the discussion should include housing growth that was not accounted for in the UWMP. Another weakness in the law is that it doesn’t have any regulatory oversight. This leaves it up to citizens to have to challenge water supply as it appears in an EIR.

The law should be expanded to require cities to keep a running total of new demand for recently approved projects that do not trigger a water supply assessment and incorporate that into all EIR’s. And while its keeping a running total of demand, it should also inform citizens on what that increasing demand will do to their monthly water allocations and rates.

This would give decision makers a little more information that might help eliminate any water shortage surprises should the increase in projected housing exceed the projected increase in the UWMP.

NBR’s other Imaginary Water

Aside from the WSA’s failure to mention new water demand from the city's ongoing housing construction, there were other problems with the Newport Banning Ranch WSA.

Aside from the WSA’s failure to mention new water demand from the city's ongoing housing construction, there were other problems with the Newport Banning Ranch WSA.

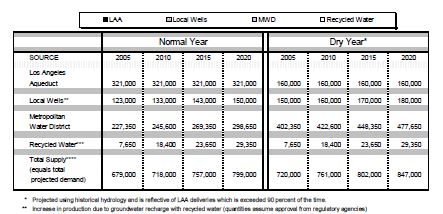

The WSA suggested that the city’s water supply would increase from 18,648 AF a year to 21,716 AF/y. This suggestion would lead the city's decision makers to incorrectly believe that supplies are increasing which would be sufficient for the projects proposed new housing. However a review of the city’s historical supply tells us another story. That there's little chance that the city's future supply will ever exceed 17,200 AF year-after-year or that it will ever see supplies exceed 19,000 Af in any one year.

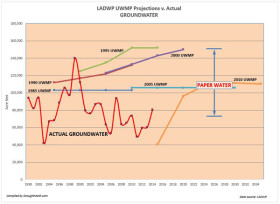

What I found was that the total well water supply was not enough to meet the UWMP projected supply. Since 1990, OCWD groundwater allocations have been averaging about 72 percent. In the last 10 years that figure has dropped to 62%.

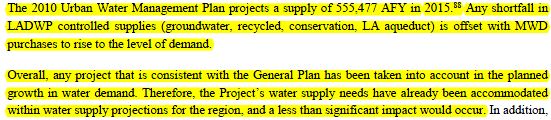

The WSA also suggested that during droughts when wells weren't producing sufficient supplies, the city would be able to make up for those shortages by purchasing imported water from MWDOC. The WSA even goes so far to state that MWDOC "was able to show that it can maintain 100% reliability in meeting direct consumptive demand under condition that represent normal, single driest, and multi dry years through 2030". However, the fact is that MWDOC doesn’t have enough water available for purchase to meet the city’s 21 percent shortfall even in wet years which is shown by the gap in the chart at the right labeled 'paper water'.

All Claims of Sufficient Water Supply Should Be Considered Suspect

The Newport Beach WSA isn't unusual. I suspect it's typical of water supply assessments produced throughout Southern California and maybe even Central California as well. The ‘Show Me The Water’ law requires that a water supply assessment be attached to the projects EIR when the project is 500 units or larger. While small and medium size projects do not require a water supply assessment, CEQA still has a requirement for an analysis on water supply in the Utilities section of the EIR.

The EIR merely has to refer to the local utilities UWMP to serve as an assessment for these projects. Whether the discussion of water supply is found in the WSA or the UWMP, there is a nearly 100 percent chance that the utilities water supply includes a substantial amount of paper water. All claims of ‘sufficient’ or ‘adequate’ water supply should be reviewed closely.

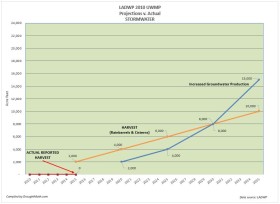

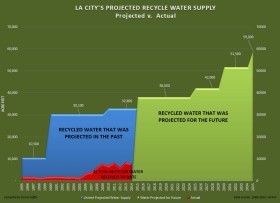

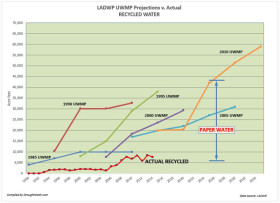

In the next sub-category, Capture and Reuse (Harvesting) is a source that is divided between rain barrels and cisterns. The department claims that Rain barrels will contribute 2,000 Af/y and up to 10,000 Af/y in 2035 to the supply. This figure is highly suspect at best because it can't be measured and it includes a lot of assumptions that makes reaching the goal unlikely.

In the next sub-category, Capture and Reuse (Harvesting) is a source that is divided between rain barrels and cisterns. The department claims that Rain barrels will contribute 2,000 Af/y and up to 10,000 Af/y in 2035 to the supply. This figure is highly suspect at best because it can't be measured and it includes a lot of assumptions that makes reaching the goal unlikely.

The DWP’s water assessments are akin to a Hollywood movie set whose front facing facades of old western towns look like the real thing but when you step through a door all you find is an empty lot.

The DWP’s water assessments are akin to a Hollywood movie set whose front facing facades of old western towns look like the real thing but when you step through a door all you find is an empty lot.

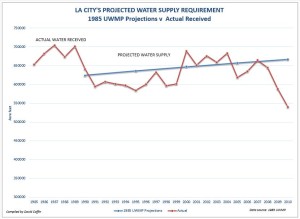

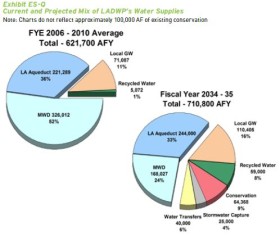

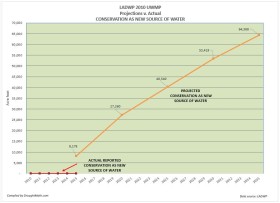

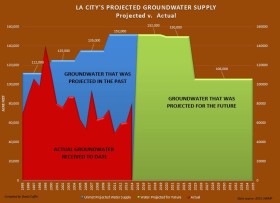

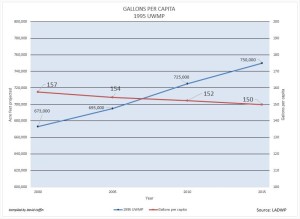

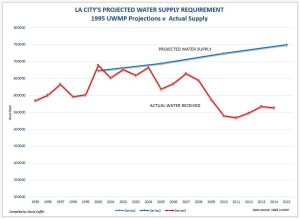

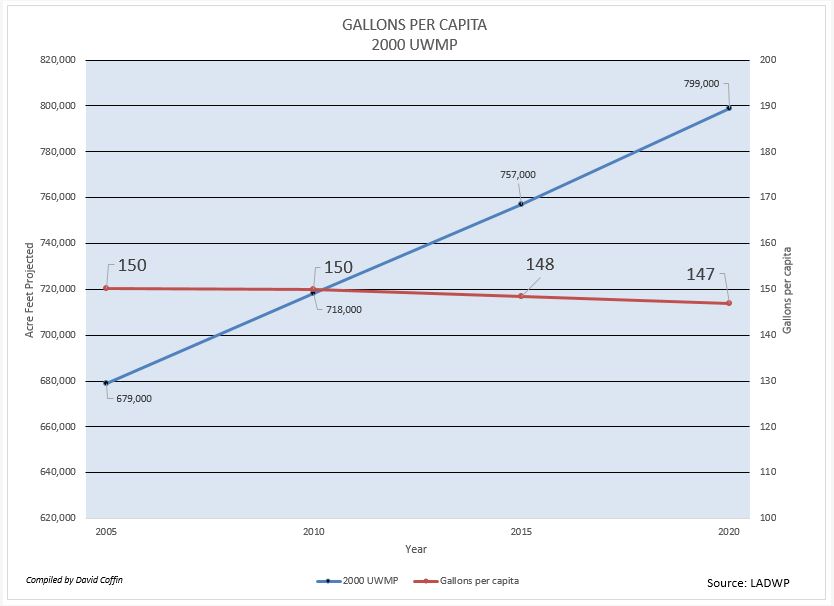

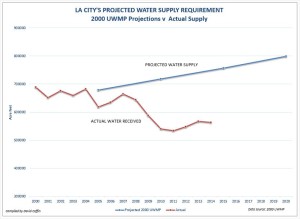

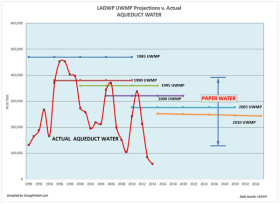

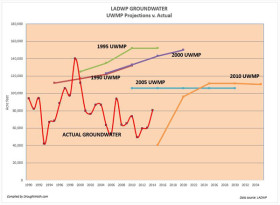

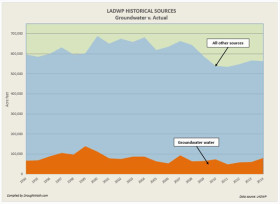

Every UWMP from 1990 till now has projected supplies that exceeded 700,000 AF but when we look back at DWP records from 1990 to 2004 we find that the city’s total supply averaged just 627,000 Af/y. Since 2005 the average has fallen even further to just 590,000 Af/y. Simply put, the DWP has never met their projections and that has steered us head-on into a drought.

Every UWMP from 1990 till now has projected supplies that exceeded 700,000 AF but when we look back at DWP records from 1990 to 2004 we find that the city’s total supply averaged just 627,000 Af/y. Since 2005 the average has fallen even further to just 590,000 Af/y. Simply put, the DWP has never met their projections and that has steered us head-on into a drought.

Over time, it became apparent that this is not simply a miscalculation but likely an intentional effort by the city to mislead the public using ‘paper water’.

Paper water is water that utilities claim they have access to, but is difficult or impossible to access for various reasons. You can't drink paper water or cook with it but you can make lots of promises with it.

The

Over time, it became apparent that this is not simply a miscalculation but likely an intentional effort by the city to mislead the public using ‘paper water’.

Paper water is water that utilities claim they have access to, but is difficult or impossible to access for various reasons. You can't drink paper water or cook with it but you can make lots of promises with it.

The