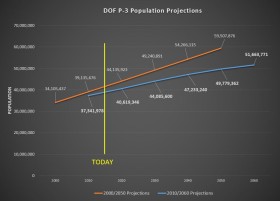

In a previous article I wrote that The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power was confronted with two conflicting demands that dates back to 1990. The department’s conflict is between providing enough water to city residents from a rapidly shrinking water supply that once averaged 680,000 Af/y and is now just over 610,000 Af/y and then also show evidence that the city’s water supply is growing to assure continued growth.

By now most of the public is well aware that there is a water shortage and that the DWP has been furiously trying to reduce the city’s residential per capita consumption by bombarding the media with accounts of shortages, imposing emergency drought restrictions, ‘drought shaming’ residents into using as little water as possible, and even paying them to tear out lawns and substitute it with drought resistant landscaping.

What the public is not aware of is that the LADWP puts on a very different face when it comes to assessing demand and assuring water supply for large new projects that consume the equivalent of 500 units or more in its Water Supply Assessments also known as WSA’s. Performing a water supply assessment is required by state law for very large projects and the department has produced more than seventy of them since 2005.

You need water? We got the water! Step Right in line.

The DWP’s water assessments are akin to a Hollywood movie set whose front facing facades of old western towns look like the real thing but when you step through a door all you find is an empty lot.

The DWP’s water assessments are akin to a Hollywood movie set whose front facing facades of old western towns look like the real thing but when you step through a door all you find is an empty lot.

Read through a WSA and you’ll be transported into a parallel world where there’s plenty of surplus water to support a projects demand for the next twenty years along with all the other planned future demand that don’t trigger water supply assessments. But look behind the report at the actual supply figures and you’ll find that like the old western town on the big screen, the WSA is a mere facade as well.

Let’s take a recent example of the large 1,444 unit downtown SOLA Village project that the LADWP recently recommended to the Board or Water and Power for approval. Keeping in mind that the City of Los Angeles is already reeling from a water shortage and has been since 1990, the DWP’s Water Resources Section concluded in the projects water supply assessment that “adequate water supplies will be available to meet the total additional water demand” and that the demand “can be met during normal, single-dry, and multi-dry water years” for the next 20 years!

The department came to this conclusion by citing water demand and supply forecasts from its own current Urban Water Management Plan. A practice that is allowed by the state but should bring to question the sincerity to the laws “Show Me the Water” hype.

The city’s past water plans have always claimed to have access to amazing amounts of water but in reality its water that can never be delivered or touched. You’ll never be able to wash your hands with it or sip it from a glass. Its imaginary water destined only for the pages of WSA's and UWMP's that are used to approve projects by decision makers.

The city’s past water plans have always claimed to have access to amazing amounts of water but in reality its water that can never be delivered or touched. You’ll never be able to wash your hands with it or sip it from a glass. Its imaginary water destined only for the pages of WSA's and UWMP's that are used to approve projects by decision makers.

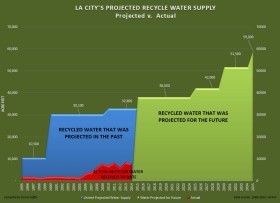

For instance, supporting the SOLA Village project, the WSA cites that over the next twenty years the department will be able to build up recycled water supplies “eight-fold” to an amazing 59,000 Af/y by 2035. The problem however is that they’ve made similar claims to this in every preceding water plan going back to 1990!

The 2010 and 2005 plans that are routinely cited in the city's WSA’s both stated that we would be enjoying 20,000 Af/y of recycled water by 2015! In reality though, we’ve only seen an average of 7,392 Af/y since 2005 and we missed the 2015 target by 13,000 AF or 4.2 billion gallons.

Touching on another source of water, the SOLA Village WSA goes on to claim that stormwater capture will increase the water supply by 25,000 AF. Stormwater capture while not new, has been getting a lot of press attention lately when it was singled out by the city as a promising groundwater recharge component that would increase supplies.

But stormwater capture along with groundwater is highly speculative and certainly not sustainable on a year-to-year basis given the whims of Mother Nature. We can only look at averages and the averages have never been good to WSA’s when you look at them historically.

Certainly the city could bump up groundwater recharge with larger catch basins but rain barrels? Seriously? The departments WSA suggests that 10,000 Af of the 25,000 AF total would be met by rain barrels and cisterns. It would take 65 million of those plastic 50 gallon barrels that cost residents about $100 to buy. I suspect that the DWP is perhaps leaning towards underground cisterns to capture some of that water. But how would we know? WSA doesn’t positively identify how many or where these cisterns will be located. It just throws out the claim. WSA’s are supposed to “Show Me the Water” as the law was named, not make empty promises.

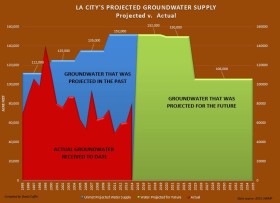

Continuing on empty promises, groundwater has always been the department’s go-to resource when you need to bump up imaginary water. The SOLA Village WSA benefits in this trend by citing wild groundwater claims that states the department will be able to deliver more than 100,000 AF year-after-year. However, so did literally every plan before it.

Continuing on empty promises, groundwater has always been the department’s go-to resource when you need to bump up imaginary water. The SOLA Village WSA benefits in this trend by citing wild groundwater claims that states the department will be able to deliver more than 100,000 AF year-after-year. However, so did literally every plan before it.

Since 1990 the DWP’s Water Systems Section has repeatedly claimed the city would be receiving an average of 100,000 AF or more each year but that was never met. The WSA doesn’t tell you that. The city’s average yield has been just 67,000 Af since 2000. The WSA also doesn’t tell you that. It doesn’t tell you that only three times since 1990 has it ever exceeded 100,000 AF. It doesn’t really tell you we really don’t have enough water for these projects.

Susceptible to Challenge

Given the way the department carelessly cites access to large sums of unobtainable water to shore up evidence of sufficient supply, this makes WSA susceptible to challenge. WSA’s are a requirement of SB 610 and SB 221 which are collectively known as the “Show Me the Water Laws” but LADWP’s WSA’s plans have not done that since 1990.